A group of blind men heard that a strange animal, called an elephant, had been brought to the town, but none of them were aware of its shape and form. Out of curiosity, they said: “We must inspect and know it by touch, of which we are capable”. So, they sought it out, and when they found it they groped about it. In the case of the first person, whose hand landed on the trunk, said “This being is like a thick snake”. For another one whose hand reached its ear, it seemed like a kind of fan. As for another person, whose hand was upon its leg said the elephant is a pillar like a tree trunk. The blind man who placed his hand upon its side said the elephant, “is a wall”. Another who felt its tail, described it as a rope. The last felt its tusk, stating the elephant is that which is hard, smooth, and like a spear. (Blind men and an elephant)

According to this source, this ‘parable’ is of Buddhist, Hindu or Jainian origin, and one version of it extends the narrative to include a conflict that breaks out among the men when they suspect the others of lying. Although this parable is supposed to reflect on the subjective nature of perception, it serves another purpose – a more literary purpose – to demonstrate how comparisons we make cannot fully establish ‘the truth’ but might be useful in understanding aspects of the subject.

Models and truth

There is no doubt that we can derive truth from the snake comparison. The flexibility of a trunk and a snake both provide some kind of physical advantage in gripping. The ear is indeed a fan, providing a cooling mechanism for an animal that must overcome the disadvantage of its large size in terms of the surface area to volume ratio with specialised surfaces that extend what was once simply an ear hole with a flap of skin to direct sound. A tree trunk and an elephant leg share the physics of the diameter required to hold up a particular weight. The skin of an elephant is as much a wall against predatory incision as any wall might be, not to mention a protective barrier to microbial infection. And, yes, the tusk is used just as a spear might be – to impale an ‘enemy’.

Comparisons are so useful to our understanding that we use them in nearly every sentence, either as direct comparisons or through metaphor. So comfortable are we with a metaphor that we hardly ever notice its use until it collides with a context in which the comparison is no longer valid – to comic effect. Our brains, in thinking in language, reflexively create a link to a known object from our experience. From there, this link can be modified and revised to provide a better internal model of the world.

It is fitting that one of our most effective metaphors is “the elephant in the room”. We know that elephants barely fit in a room, so those not noticing it must be especially blind since it occupies the whole space. Moreover, elephants so rarely reside in rooms that to have missed its presence is to have not noticed something that should ‘stand out like a sore thumb’. And elephants, in most contexts, simply do not have to announce their presence – their size makes them obvious and their silence makes them safer. Truly, someone unable to perceive this elephant has a peculiar kind of blindness.

It is probably the substance of a thesis at a high academic level to contemplate why people are wantonly blind or why we are so ready to make comparisons that serve us by providing ready models. I’m not going to pretend I have properly investigated either of these theses. Instead, I am asking you to follow me in examining how the use of analogies as a comparison can lead one to a reality that is nothing ‘like an elephant’. Tempting as it may be to indulge in cheap politics and simply generate a meme of some current leader as adequate evidence of how easily analogy can be misused, this would be a bit lazy and not fair to analogy.

Religious discourse and analogy

Religious discourse is rich in analogy. In describing how the ‘church’ should operate in unison for a single purpose, ‘head’ and ‘body’ are employed by Christian scholars to model what is perceived to be reality. Except for those who insist on transubstantiation, the ‘body of Christ’ in the Eucharist is intended metaphorically to indicate how Christians can be the embodiment of any of the principles or missions espoused by Jesus and Jesus can be the head in the sense of a source of guidance or inspiration.

What is interesting about this metaphor is not necessarily its ‘spiritual significance’, but the ease with which it can be manipulated to render itself as the rationale for any number of practices. If the head controls the body, so, too might we expect the principles or missions espoused by Jesus to control us – to the point of neglect of our own desires. In other words, by using this analogy, we can appear to make a case for a human Christian automaton and, by extension, divine control.

It does not take much imagination to determine the intent of the first interpretation. The analogy, if accepted, will cause people to relinquish their will and search for this guidance. They become compliant. This serves the powerful well, as it has throughout the last 2000 years of history.

On the other hand, the model can be used to construct a ‘visceral verses cerebral’ concept of the church that means that Christians can derive inspiration from the ‘head’ but this needs to be made visceral in life. Hence, Jesus will inspire ‘good works’ and Christians need not relinquish their agency.

And “therein lies the rub” (William Shakespeare, “Hamlet”).

The point is not that one of these models is ‘the truth’. Clearly, acceptance of one model or the other may be a good indicator of how you will vote or what you will think about same sex marriage.

More importantly, if we accept the metaphor as having a validity both beyond its literary intent or beyond what can properly be derived from evidence or experience, the metaphor takes on ‘a life of its own’ and, in the manner of metonymy, can come to be accepted as an authority in itself, something to listen to and follow, or, at the very least, to have an agency of its own.

No-one doubts that Queensland will win the next State of Origin rugby league match, even though only a handful of them, some now not Queenslanders at all, actually play. What we mean is that there is an emergent quality of ‘us’ as a group of people which can be identified and manipulated to inspire extraordinary effort, not to mention a religious fervour and the spending of truckloads of money. To dismiss this as ‘just hype’ is to ignore the evidence in the behaviour of people. Simply attend one of these matches and try to argue that this quality is not visceral. I did attend one such match – and I cannot recall anything quite so simultaneously exhilarating and terrifying.

So, in simple terms, our behaviour can be manipulated by adopting a model which may or may not be reflected in reality.

CS Lewis – an exemplar

At this point, a segway to a notable Christian author, CS Lewis, is not entirely illogical. In particular, I want to focus on his text, “Sexual Morality”, illustrated as one of a series on YouTube, taken from his work “Mere Christianity”. I will avoid my inclination to label Lewis acolytes as not Christian at all, but Lewisian – that is, they happily extend the Biblical canon to Lewis’ works and are happy to accept Lewis’ judgement over Jesus. I will also avoid my inclinations to label Lewis as a solid representative of British imperialism. Or the general observation that he is given to sloppy binaries. These and other criticisms are not relevant to this critique.

I want to focus on how Lewis constructs a metaphor and sustains it throughout his text to the point where one must either simply reject the premise or accept the conclusion. As is the way with so much apologetics, this bi-modal outcome is particularly marked, probably intentional, deeply conservative and dangerous.

The focus here is the ‘machinery’ of persuasion available in metaphor and how it is abused.

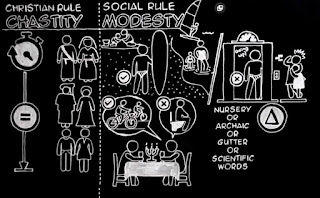

Lewis’ sociological analysis is unremarkable and barely controversial. It is true that modesty standards vary by culture, time and circumstance. We need not trot out the myriad of research which demonstrates that. And, plainly, various streams of religious practice reflect chastity edicts made predominantly by old men to imprison women. Such is the far too common abuse of religion.

Female genital mutilation is a case in point. This practice grew out of superstitious and ignorant practices of circumcision, almost certainly from rural Africa and the Middle East. Still widely practised in Africa, despite criminalisation and education, FGM does not follow religious boundaries – it is, in fact, practised in nearly every religion that has arisen or been imported into this area. It is, of course, a decisive symbol of the dominance of the parent over the child in terms of sexuality.

Conservatism and sexuality

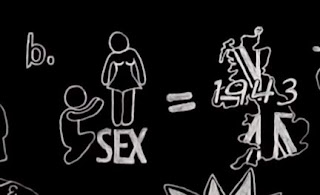

Lewis first touts chastity as the Christian ‘rule’, distinct from social rules that prohibit exposure or bad language in certain contexts. Lewis’ boundary between the two social imperatives only illustrates, again, a mind locked into boundaries. But his propositions are not controversial and easy to accept as sociological fact. Thus far, we are not invited to make a comparison by way of metaphor. Those who disagree with the notion of chastity probably welcome its modern demise, perhaps not so obvious to Lewis in 1943.

If we focus on the words, rather than the illustrations of the doodle, we hear a continuation of his sociological analysis, albeit with a particularly ‘English’ orientation. Not giving offence is valued and those who display sexuality for ‘shock’ impact are considered socially irresponsible. I guess most people would agree to some extent. Like all good conservatives, Lewis seeks to assert that there is a continuous ‘right’ (Christianity) and our own instincts are wrong. The confusion experienced in each generation about the standards that are acceptable is real. Lewis’ conclusion that this means “we hardly know where we are” is unproven and part of the constant conservative refrain that ‘dropping’ standards leads to chaos.

But, this is not the main game. It is easy enough to dismiss these views as conservatism – a conservatism that is fast losing credibility. What Lewis needs is a model to support his assertions.

Making a model

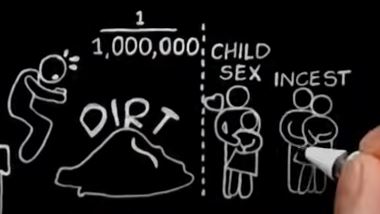

At around 4 minutes into his speech, Lewis looks to an analogy to work his persuasion. It can be scientifically established that both eating and sex are necessary for the survival of the species, that appetites for each are on-going and natural and that the ritualisation and institutionalisation of both is what we might expect.

At this point, we might have already begun to develop a model in our head that says that novelty in sexuality, as in food, is both enticing and fraught. A ‘liberal’ would emphasise that few people eat the same food day after day and that novelty in sexual satisfaction is quite acceptable. Conservatives would argue that we are better served, to maintain a society where demand for food is stable, to maintain a consistent diet, lest we have an upset tummy. It would seem that evolution and experience support this idea. The metaphor, as with all metaphors and similar literary devices, invites us to form a model. This model is tested against experience and usually gains some credibility or not in our mind. We conduct a ‘pub test’.

The art of persuasion is in misdirection. As Shakespeare said,

In law, what plea so tainted and corrupt but being seasoned with a gracious voice obscures the show of evil? The seeming truth which cunning times put on to entrap the wisest.”

(William Shakespeare, “The Merchant of Venice”)

The misdirection here is the statement of something uncontroversial and acceptable. Lewis posits that a man might over-indulge, with little consequence and natural limits provide a barrier to excess, such as the size of the stomach. As with most amateur magic, our thoughts follow the analogy. In that we accept the point that a little indulgence in food has minimal consequences, we are can just as easily accept the counterpoint that indulgence in sex might be dangerous. The ‘set’ here, against which we will now measure eating and sex, is that one appetite is benign and the other fraught with peril.

We can easily rebut the proposition that is asserted – sex automatically leads to overpopulation without the intervention of contraception. With contraception, sex can be common but with consequences. But matter how we construct our rebuttal, we have been led into a landscape where some natural desires are deemed naturally constrained and others are not and these two desires lead, almost inevitably, to social ills on very different scales. It will be easy to see that a little constraint will staunch the vomiting, discomfort or unwanted weight gain of overeating. But we fear that even a mild indulgence in sex is critical. As, indeed, it is, given the dire social consequences of unwanted pregnancies.

The argument is weak. The social consequences of sex in Lewis’ era are nothing like that of the modern world. So, it should be easy to simply dismiss Lewis on sexual morality. Relax. Lewis is just out of date. We can move on. We have protection.

But, although you think you have moved on, you have not. Lewis has already taken you to a place where your thinking can be manipulated by a metaphor.

Make the model work

The next stage of misdirection is to move to an equivalence. Lest we think that both appetites, sexual and food, are equivalent and manageable, Lewis throws up a rabbit drawn from a hat to distract. Lewis proposes that an exposure of a piece of mutton on a plate would not draw an audience, but a naked woman regularly does. Our mind follows the analogy, suggesting that sexuality has a potency that food does not. Thus, it could be dangerous.

Since our mind set is already on food and sex, we can easily accept this point. Ironically, if Lewis had been transported in time to our age, he may have realised that food porn is as enthusiastically heralded as naked flesh – maybe even more so. By this stage in the extended metaphor we are firmly persuaded that sexuality and eating have both parallel and divergent qualities, but the underlying appetite and management of appetite is consistent. It is not difficult to arrive at the 12 Rules for Life premised in our knowledge of food.

1. Only eat what you need.

2. Food is for sustaining the body, not treating casually.

3. Don’t nonchalantly throw food around.

4. Eating at mealtimes is better than on the go.

5. Not all food is wholesome.

6. There are traditions of good eating. Observe them.

7 …

Without knowing Jordan Peterson (and my attempt to mock his rules for life), you get the picture. Sex, it would seem, lends itself to good and bad practises.

The thin end to the thick wedge

It is not the manner of Lewis to leave a metaphor ‘hanging’. Having procured our attention and acceptance, he is now free to enumerate the evidence for chaos. Without being distracted by arguing against his absurd conservative and dated views, one can see that this is, indeed, the opportunity to refine the metaphor. Against the litany of potential evils that sex can invite, the benign instinct to eat can be equally a response to starvation as it might be simple gluttony.

Given the almost universal difficulties people have in eating sensibly, the forgiveness for abuse is universal and expected. The chaos of rampant sexual activity is also universal.

A complete analysis of the continuing deployment of this metaphor by Lewis is possible, but will probably bore you. Watch the video for yourself and see how this metaphor takes on a life of its own and becomes the authority with which one can discipline sexual desire. Food perversion is rare; sexual perversion is common. Food assault is not a thing; sexual assault is. The longer we linger in this binary model, the more we can demonise sexual desire. Lewis no longer has to build an argument to convince. He simply leverages our perception of food and sexuality that we willingly accepted.

No longer needing to make explicit the ‘reasonableness’ of the constraint argument, a full explication of a divine ‘final solution’ follows upon the logic and the impending doom that will come out of chaos. I probably won’t be able to resist chocolate and will continue to be fat. I probably won’t be able to resist naked women and will continue to watch porn. How will I be saved? In the true Salvationism mode, Lewis calls upon this greater wisdom from on high to deliver us.

The power of metaphor

No real or salient analysis has really been conducted by Lewis either on eating or sex. Instead, we were lured into the Salvationist space by a clever metaphor – “tainted and corrupt but being seasoned with a gracious voice obscur(ing) the show of evil”. No-one could fault the art of Lewis the magician. And no-one should believe themselves immune from the “seeming truth which cunning times put on to entrap the wisest.”

For those not trapped in religious dogma or practice, this may seem a trivial exposition of Lewis’ techniques. You might know already that sexual assault is a social phenomenon more closely related to power than sex. You may have already dismissed the supposed extrapolation of sexual desire to sexual exploitation.

But, if we are to properly understand those who are entrapped, we need to understand how the magicians that lead them work.