On the 12th of April, ASPI (Australian Strategic Policy Institute) launched the annual report by the IEP (Institute for Economics & Peace). The report gives credible data on global terrorism, with its key publication being the ranking of countries according to the impact that terrorism has had on it.

One wonders why the IEP needs ASPI to launch its report, as IEP director Dr David Hammond did little more than simply highlight various elements of the report. Expert contributions were interesting but did not really add much to the report except, perhaps, to give perspectives from other countries; which, of course, does nothing to change the underlying facts of terrorism.

Based on the report and those before it (back to 2014), I asked a question at the launch which was completely relevant and addressed the successes and failures of counter-terrorism, as objectively shown in the data. This is the question.

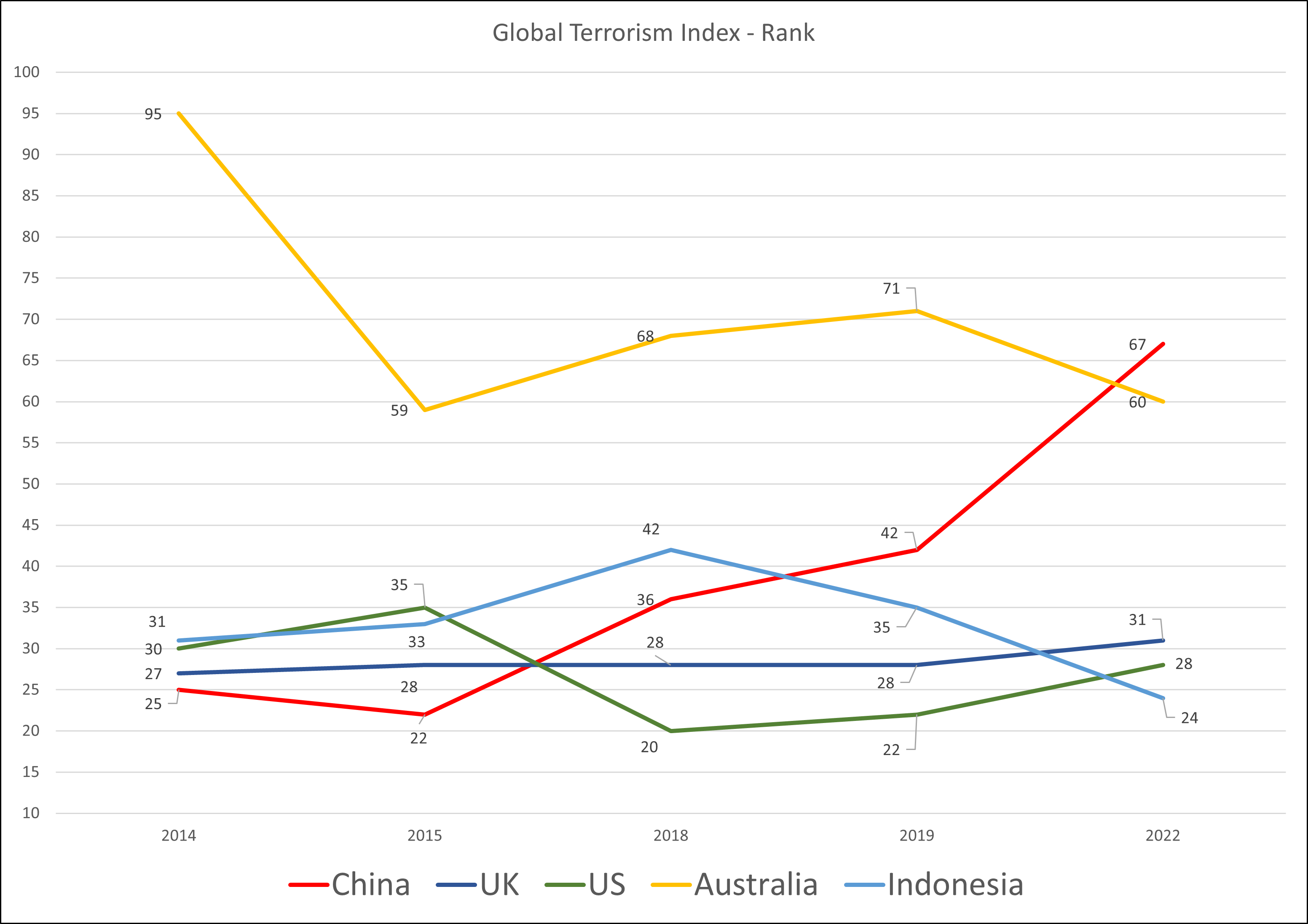

In 2014, we find 4 countries in a comparable position on the GTI – US, UK, China, and Indonesia, at around rank 30. This indicates significant challenges in managing terrorism in those countries. Australia was ranked 95, an enviable position to be in.

If we consider the UK, we find that from 2014 to 2022, the rank stays stubbornly on 30 + or – 2. The US position drifts gradually down to rank 20, indicating that terrorism in this country increased. Only in the last 3 years has this improved, mostly in line with global trends.

Meanwhile, Australia plunged 36 places from 2014 to 2015, still much more favorable than both the US and UK but has, as with the UK and US, stayed stubbornly at around 60. Indonesia shows a steady rise until 2018 when it starts to drop in line with global trends.

The miraculous story is China. From a low 25 (below US, UK, and Indonesia), China has steadily risen, year on year, through the rankings to now be 67th place, passing Australia.

This represents a change of 42 positions over 8 years.

China’s record can only be described, objectively, as incredibly successful. Its program of clear intent, selective detention, surveillance, poverty alleviation, economic development and strong determination has produced results that are, surely, the envy of the world.

In view of the relentless campaign by western media, academics, and ASPI to discredit this achievement, can you reflect on why you think ASPI has taken such a negative line and whether, in the final assessment, their campaign against China has been grounded in poor research and lack of objectivity?

There was a mistake in the question that was a result of accidentally writing what I intended for an earlier paragraph. I should have written “Indonesia shows a steady rise until 2018 when it starts to drop, against global trends.” In any case, this was a minor point, included to show that other large Asian countries still face a challenge.

In graphic form, this looks like:

The question goes directly to the issue that is obvious. Despite incredible expenditure and political posturing, the UK and US have been singularly unsuccessful in combatting terrorism while China, in contrast, has been spectacularly successful. Time to celebrate that one country has found a way of keeping its citizens safe.

My question was the first to be put but Katja Theodorakis, Head of Counterterrorism Program made the decision to censor it on behalf of ASPI and its sponsors – US arms manufacturers and two foreign governments – UK and US. One wonders how the ASPI program can be labelled as ‘counterterrorism’ when those involved in the program demonstrate contempt for real discussion on major successes.

In line with the dishonesty and complete lack of integrity that ASPI displays as its normal mode of operation, this launch proved to be a complete farce. As global conflicts and climate change make ever increasing demands on populations, providing ample breeding grounds for terrorism, ignoring successes and failing to properly analyse the basis of their success will be at our own peril.